ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT SARCOMAS(BONE& SOFT TISSUE CANCER)

Sarcomas are a heterogeneous group of rare malignancies originating from mesenchymal tissues, which comprise connective tissues, muscles, bones, and fat. Despite their rarity, sarcomas are highly aggressive, with a significant impact on patients’ quality of life and survival. This comprehensive research aims to delve into the various aspects of sarcomas, including epidemiology, etiology, classification, clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY.

Sarcomas are relatively uncommon cancers, accounting for less than 1% of all adult malignancies. The incidence varies by subtype, with osteosarcoma being more prevalent in adolescents and young adults, while soft tissue sarcomas are more common in older adults. Geographic variations in incidence have been observed, suggesting potential environmental risk factors.

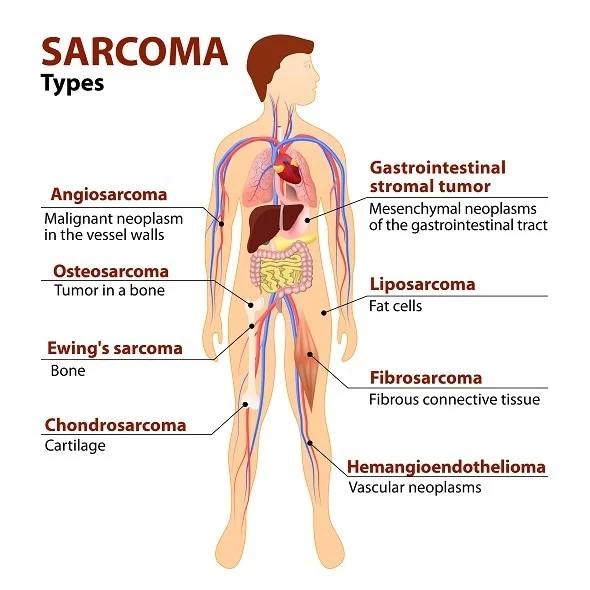

CLASSIFICATION OF SARCOMAS.

Sarcomas are classified into two major categories: soft tissue sarcomas (STS) and bone sarcomas. Each category encompasses various subtypes based on the tissue of origin and specific histological characteristics.

- Soft Tissue Sarcomas (STS):

- Liposarcoma: Arises from adipose (fat) tissue and is one of the most common types of STS in adults.

- Leiomyosarcoma: Originates from smooth muscle cells, typically in the uterus, gastrointestinal tract, or blood vessels.

- Rhabdomyosarcoma: Develops from skeletal muscle cells and is more common in children.

- Angiosarcoma: Emerges from the endothelial cells lining blood vessels and lymphatic vessels.

- Synovial Sarcoma: Often found near joints and tends to occur in adolescents and young adults.

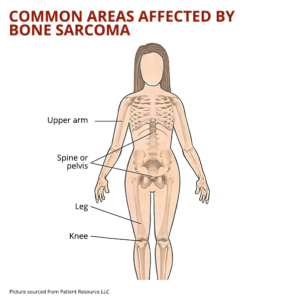

- Bone Sarcomas:

- Osteosarcoma: The most common primary bone cancer, primarily affecting adolescents and young adults. It usually occurs in the long bones, such as the femur or tibia.

- Ewing Sarcoma: Affects bone or soft tissue, predominantly in children and young adults. It most commonly occurs in the pelvis, femur, or chest wall.

- Chondrosarcoma: Originates from cartilage cells and is more common in adults. It typically occurs in the pelvis, femur, or shoulder.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION(pattern of symptoms.)

The clinical manifestations of sarcomas vary depending on the tumor’s location, size, and subtype. However, common symptoms include:

Soft Tissue Sarcomas:

- Painless lump or swelling, which may become painful as the tumor grows

- Reduced range of motion if the tumor is near a joint.

- Neurological symptoms such as numbness or tingling if the tumor compresses nerves.

Bone Sarcomas:

- Persistent bone pain that may worsen at night or with activity.

- Swelling and tenderness over the affected bone.

- Pathological fractures due to weakened bone structure.

Given the non-specific nature of these symptoms, sarcomas are often diagnosed at an advanced stage when the tumor has grown significantly or metastasized.

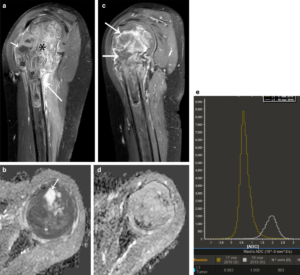

DIAGNOSTIC METHODS (detection)

The diagnosis of sarcomas involves a combination of imaging studies, biopsy, and histopathological examination.

Imaging:X-rays:

Initial imaging modality for suspected bone sarcomas. It can reveal bone destruction, new bone formation, and periosteal reaction.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Preferred for soft tissue sarcomas and for evaluating the extent of bone sarcomas. MRI provides detailed information about the tumor’s size, location, and relationship with surrounding structures.

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Useful for detecting lung metastases, which are common in bone sarcomas.

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Scan: Assesses the metabolic activity of the tumor and helps in staging and monitoring treatment response

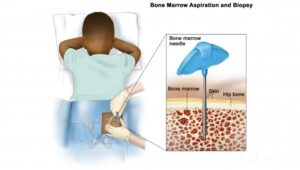

Biopsy:

A biopsy is essential for a definitive diagnosis. Core needle biopsy or incisional biopsy is typically performed to obtain a tissue sample for histopathological analysis.

Histopathology:

The tissue sample is examined under a microscope to determine the sarcoma subtype and grade. Immunohistochemistry and molecular testing may be employed to identify specific genetic markers and translocations.

TREATMENT.

The treatment of sarcomas is multidisciplinary, involving surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy.

Surgery:

Surgical resection with clear margins is the primary treatment for localized sarcomas. The goal is to remove the tumor entirely while preserving function.

Limb-sparing surgery is preferred for extremity sarcomas, but amputation may be necessary if the tumor is extensive or invades critical structures.

Radiation Therapy:

Preoperative or postoperative radiation therapy is often used in conjunction with surgery to reduce the risk of local recurrence.

For unresectable tumors, radiation therapy may be the primary treatment modality.

Chemotherapy:

Chemotherapy is particularly effective in certain sarcomas, such as Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma. It is used in both neoadjuvant (preoperative) and adjuvant (postoperative) settings.

Common chemotherapeutic agents include doxorubicin, ifosfamide, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide.

Targeted therapies have emerged as a promising approach for treating sarcomas with specific genetic mutations or translocations.

- Imatinib: A tyrosine kinase inhibitor effective in treating gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) by targeting the KIT and PDGFRA mutations.

- Pazopanib: Approved for the treatment of advanced soft tissue sarcomas, targeting angiogenesis pathways.

Immunotherapy:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab, have shown some efficacy in certain sarcoma subtypes, particularly those with high mutational burden or expression of PD-L1

PROGNOSIS.

The prognosis for patients with sarcoma varies greatly depending on the type, stage, and location of the tumor, as well as the patient’s overall health. Early detection and treatment are crucial for improving outcomes.

CONCLUSION.

Sarcomas are a heterogeneous group of cancers with complex biology and varied clinical presentations. Despite being rare, they pose significant treatment challenges due to their aggressive nature and the potential for late diagnosis. Advances in molecular biology and genomics are paving the way for more precise diagnostic tools and targeted therapies, offering hope for improved outcomes in sarcoma patients. However, ongoing research is essential to unravel the intricacies of sarcoma biology and to develop novel treatment strategies that can effectively combat these formidable cancers.

References

Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, Enzinger FM. Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013.

Mertens F, Antonescu CR, Hohenberger P, Ladanyi M, Modena P, D’Amore ES. Sarcomas. Springer; 2017.

Grimer R, Judson I, Peake D, Seddon B. Guidelines for the Management of Soft Tissue Sarcomas. Sarcoma. 2010;2010:506182.

ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working Group. Bone sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25 Suppl 3

Penel N, Coindre JM, Bonvalot S, et al. Management of desmoid tumours: A nationwide survey of labelled reference centre networks in France. Eur J Cancer. 2016;58:90-6.

Gaspar N, Hawkins DS, Dirksen U, et al. Ewing Sarcoma: Current Management and Future Approaches Through Collaboration. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(27):3036-46.

Widemann BC, Italiano A. Biology and Management of Osteosarcoma and Ewing Sarcoma: A Review from the Molecular Perspective. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;62:31-44.

Schoffski P, Ray-Coquard I, Cioffi A, et al. Activity of eribulin in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma: A Phase 2, open-label, single-arm, non-randomised study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(11):1045-52.

Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Jones RL, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ripretinib Versus Sunitinib in Patients with Advanced Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor in INTRIGUE: A Phase III, Randomized, Open-Label Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(15):1557-68.

Written by Fawzi Rufai, Medically Reviewed by Sesan Kareem